Ethnographiska, historiska och statistiska anmärkningar. 015

Title

Ethnographiska, historiska och statistiska anmärkningar. 015

Description

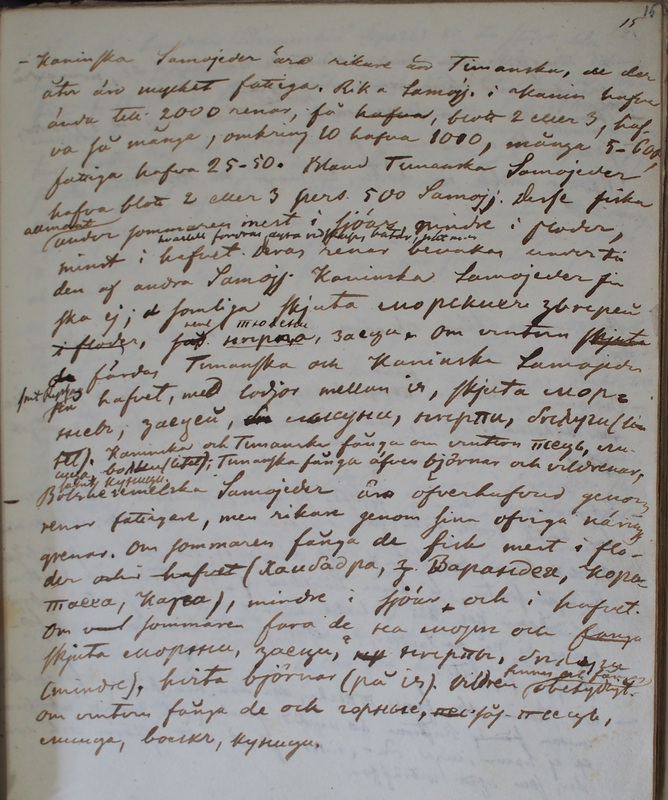

| Kaninska Samojeder äro

rikare än Timanska,

de derBefore the mid-19th century, when Castrén was travelling in the European Arctic, large-scale nomadic reindeer herding was developing fast, but, as shown by Krupnik (1976; 1993: 171–80), it never meant a stable number of reindeer herds, but rather there was a constant change in the number of herds as a result of ecological, political, and economic factors. In addition, it is important to note that instead of a total shift, there were always herders with fewer reindeer, which also means more reliance on fishing and hunting. The Kanin and Timan Nenets seem to have shifted to a pastoralist economy before the Bolʹšezemelʹskaja ones, which is why they also had more reindeer in the early 19th century. (See Tuisku 1999: 58–65; Stammler 2005: 62–66; Anderson 2014; Stepanoff et al. 2017; Dolgich 1970: 23–25.)

åter äro mycket fattiga. Rika Samojj[eder]. i Kanin hafver ändå till 2000 renar, få hafva blott 2 eller 3, haf- va så många, omkring 10 hafva 1000, många 5-600 fattiga hafva 25-50. Bland Timanska Samojeder hafva blott 2 eller 3 pers. 500 Samojj.

[Samojeder] Desse fiskaThe number of reindeer is one indicator of the development of a large-scale pastoralist reindeer economy. The variation in the sizes of the herds is not only a marker of economic stratification, but rather indicates that there were different kinds of economic strategies among the Nenets. Those who owned only a few reindeer used them as draught animals and focused on fishing and hunting, and were most probably hired by Russian or Komi merchants. With a few hundred reindeer, one could live by selling hunting products, whereas with thousands of reindeer, there was a possibility of living on reindeer products alone. (See Krupnik 1976.) As noted recently, the number of reindeer not only gave prestige and enabled movement but also tied the large-scale reindeer herders to the tundra and the herd (Golovnev 2004; Stepanoff et al. 2017). It is rather perplexing how fast the combination of large herds and the ability to move in the tundra became emblematic of the Nenets way of life, TN ненэй илеңгана, although pastoralism was still developing in the early 19th century. This is most probably related to the prestige related to large herds, but also their value in exchange and in hunting (Stepanoff et al. 2017). Additionally, there is a tendency in 19th-century explorers, such as Castrén, to describe reindeer herding as the emblematic and immemorial form of subsistence, which for a long time obscured the transition that was taking place. (For the development of reindeer herding, see also Losey et al. 2021; Anderson et al. 2019; Stépanoff 2017.)

allmänt under sommaren mest i sjöar mindre i floder, hvartill fordras dyra redskap, båtar, mat m.m. minst i hafvet.

Deras renar bevakas under ti-Fishing has a significant role in Nenets subsistence. Fishing is focused on the rivers and lakes, and is especially important for the communities living near large rivers such as the Pečora, Pur, and Nadym. Fishing is carried out with the help of seines, nets, traps, and weirs. It is important for food, but also for extra income. In the 19th century, Nenets also worked as fishermen for Russian merchants and were part of fishing communities; see note [af andra Samojj.] and [Mezen merchants]. (Chomič 1966: 78–80.)

den

af andra Samojj[eder].

Kaninska Samojeder fi-The Nenets formed communities called Ru parma, TN парм (reindeer herding) or Ru edoma, TN нядʹʹма (fishing and hunting sea mammals) in order to manage their seasonal hunting and fishing practices. According to Maslov, the communities were of close or more distant descent and often included both rich and poor families in terms of reindeer. During fishing and hunting, the reindeer herds were left within the larger herds of communities with more reindeer. (Maslov 1934; Terleckij 1934; Tuisku 1999: 82–83; similar in the Taz (Forest Nenets) region; see Lehtisalo 1956: LV–LVI.)

ska ej, somliga skjuta морскихъ зверей i floder neml. тюлены,

Ru tjulenʹ, TN явʹ сармик, няк ʻseal’.

нерпа,

Ru nerpa, TN няк ʻringed seal’ (Phoca hispida Schreber).

заеца.

Om vintern skjuta deRu morskij zajac, TN ңартиʹ ʻbearded seal’ (Erignathus barbatus Erxleben).

färdes Timanska och Kaninska Samojeder s[a]mt Ryska till hafvet, med lodjor

mellan is, skjuta

Ru lad’ja or lod’ja is a wooden sailing and fishing vessel with pole masts and oars. The lodjas, together with larger karbas vessels, were widely used by the Pomors (MES 1991: lad’ja).

моржевъ,

Ru morž, TN тивтей ʻwalrus’ (Odobenus rosmarus Linnaeus).

заецей, лысуни,

нерпи,

Ru lysun (also Grenlandskij tyulenʹ), TN няк ʻGreenland seal’ (Phoca groenlandica Erxleben).

белуги

A maritime economy, which was practised in the 17th century by communities living on the Arctic seashores, had disappeared by the 18th century, only to undergo a revival at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries. Krupnik has proposed that the hunting of sea mammals in the 19th-century European Arctic was mainly a joint practice of the Nenets and the Russian Pomors, which is also implied by Castrén. Consequently, this does not represent the earlier indigenous maritime economy, but a seasonal practice based on commercial and collective hunting. (Krupnik 1993: 202–210)

Kaninska och Timanska fånga om vintern псецъ,

ли-Ru pesec, TN ңохо ʻArctic fox’ (Alopex lagopus Linnaeus).

сица, волки

(litet); Timanska fånga äfven björnar och vildrenar,Ru volk, ТN сармик ʻwolf’ (Canis lupus Linnaeus).

samt куници |

The Kanin Samoyeds are richer than those of Timan, who again are very poor. The rich Samoyeds in Kanin own up to 2000 reindeer, a few have only two or three, about ten [Nenets] have 1000, many have 5-600, and the poor own 25-50. Among the Timan Samoyeds only two or three persons own 500 [reindeer]. These Samoyeds commonly fish during the summer, mostly in lakes, less so in rivers, for which expensive equipment, boats, food, etc., is required; the least [fishing is done] in the sea. Their reindeer are guarded during the time [of the fishing] by other Samoyeds. The Kanin Samoyeds do not fish; some shoot sea mammals, in other words seals (seal, ringed seal, and bearded seal). In winter the Timan and Kanin Samoyeds and the Russians travel to the sea, using lodya boats to move through ice, and shoot walruses, seals, and whales. In winter the Kanin and Timan [Samoyeds] hunt Arctic foxes, foxes, and wolves (a little); the Timan also hunt bears and wild reindeer, as well as pine martens. |

| Bolshezemelska Samojeder äro öfverhufvud genom renor fattigare, men rikare genom sina öfriga närings- grenor. Om sommaren fånga de fisk mest i flo- der och i hafvet (Хаибадра,

Chajpudyr Bay, situated on the western side of the Yugor Peninsula. N68°30′14″ E59°31′54″

Варандея,

Varandej Bay, situated on the western side of the Yugor Peninsula. N68°44′53″ E57°59′48″

Коратаеха

The River Korotaicha flows into the Pečora Sea on the west coast of the Yugor Peninsula. (GVR)

Кара),

mindre i sjöar och i hafvet.The River Kara flows into Kara Bay on the east coast of the Yugor Peninsula. According to Schrenk, TN ”Harájjagha oder Harájagha, d.i. der bugreiche Fluss [Хараяга]” (GVR) (Schrenk 1848: 463; Šrenk 2009: 312)

Om sommaren fara de на море och fånga skjuta моржи, заеци, нерпы, белуги

Ru belucha, ТN вэбарка ʻwhite whale, beluga’ (Delphinapterus leucas Pallas).

(mindre), hvita björnar (på is), vildren finnas och fångas obetydligt. Om vintern fånga de ock горные fög[lar]., псецъ лисица,

волкъ,

Ru lisica, ТN тëня ʻfox’ (Vulpes vulpes Linnaeus).

куници.

Ru (sosnovaja) kunica, TN иңгней ʻpine marten’ (Martes martes Linnaeus).

|

The Bol'šezemel'ja Samoyeds are in general poorer when it comes to reindeer, but richer when it comes to their other sources of livelihood. In the summer they fish, mostly in the rivers and in the sea (the Chaibadra, Varandeja, Korataecha, Kara), less so in the lakes and in the sea. In the summer they travel to the sea and shoot walruses, seals, whales (smaller ones), and polar bears (on the ice); there are wild reindeer, but hunting them is insignificant. In winter they also hunt mountain birds, Arctic foxes, foxes, wolves, and pine martens. |